There is only one such village in Bangladesh where such toys are made. Approximately 200 families in the village are producing tomtoms, transforming each residence into a hub of artisanal activity. Thus, a network of small-scale cottage industries has emerged

Two sticks are attached to the cart, producing a distinctive sound when pulled by children. Hence, the name ‘tomtom car.’ Photo: Rajib Dhar

“>

Two sticks are attached to the cart, producing a distinctive sound when pulled by children. Hence, the name ‘tomtom car.’ Photo: Rajib Dhar

As the sun peeked through the clouds of the winter morning, each household in the village started to bustle with activity in their courtyards, basking in its warmth.

Upon entering the village, one is greeted by the sight of vibrant tomtom and tortori cars being crafted out of wood, by people working from mud houses. These toys are staples at fairs. The air is filled with festivity as wooden cars, wheels, birds, trucks, violins, sarindas, ghinnis, and an array of other toys are made.

Women and young girls of the households meticulously paint sticks with colours, create intricate Alpana designs on paper, working inside their courtyard. Others craft toys out of wood, bamboo, and paper.

The village is Kholash, or Tomtom Village. It is 20 kilometres west of Bogura town, at Dhaper Hat, Dupchanchia.

There is only one such village in Bangladesh where such toys are made. A cottage industry centred on toymaking has taken root within the households of this village. Approximately 200 families in the village are producing tomtoms, transforming each residence into a hub of artisanal activity. Thus, a network of small-scale cottage industries has emerged.

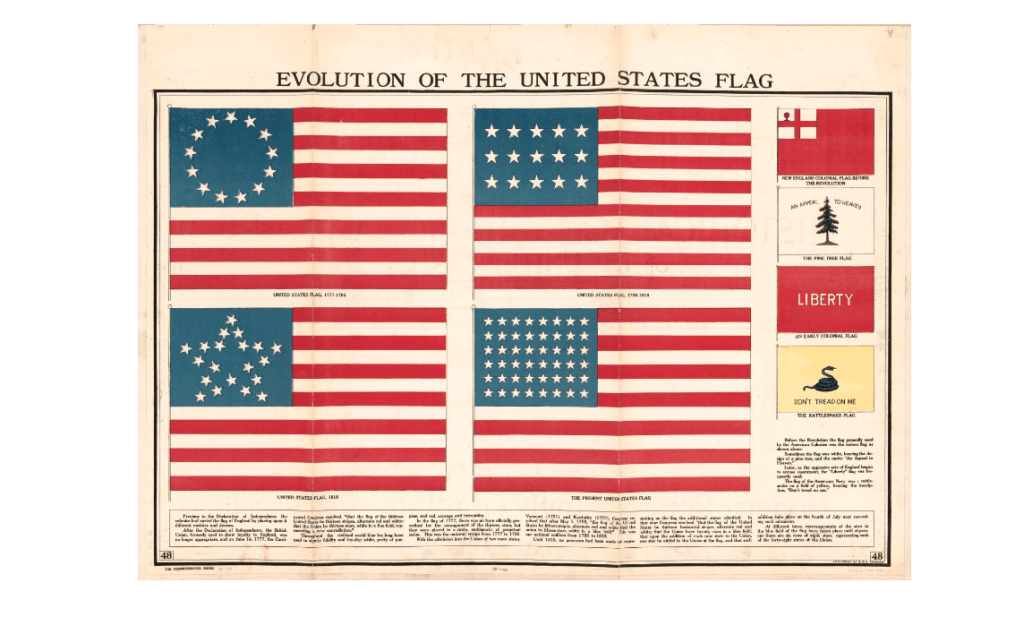

The prevalence of tomtom cars among toys manufactured in the village, coupled with their widespread popularity across the nation, has earned the village the name of ‘Tomtom Gram’ among the locals, while ‘Kholash Gram’ is its official description in documents.

Throughout the year, craftsmen in this village diligently produce these traditional toys, showcasing and selling them at various fairs and festivals across the country. However, the fervour intensifies during the Bengali New Year festival notably.

In total, around 10,000 people are engaged in the profession of toy-making. Annually, these artisanal centres generate a turnover of approximately Tk100 crore.

As we walked down the road leading to Kholash Purbo Para, we noticed rows of mud houses lining the path. From one of the doors, we observed someone delicately cutting thin strips of bamboo. A small clay lamp sat on the side. Three women were seated together, deeply engaged in their work. They glanced up with mild curiosity as we approached.

In response to our query, they explained that crafting and selling these toys is their family business, sustained throughout the year.

Around 60 to 70 years ago, a resident of this village named Kurano initiated the production of tomtom toys. He was lost during his childhood but was later found by some Biharis from Syedpur, who taught him the craft of making tomtom toys.

Upon returning to Kholash Gram, Kurano – now a grown man – began crafting tomtom toys and teaching others in the village. Thus began the history of tomtom toy production in the village.

Tomtom is still an attraction at village fairs, symbolising a heritage and cultural essence of Bangalis. Particularly during the Bangla New Year festivities, when fairs are hosted in cities and villages nationwide, the prominence of these toys is evident.

As asserted by traders and craftsmen from Bogura, the production of tomtom toys is exclusively centred in this particular village in Bogura district.

These tomtom toys are meticulously crafted in small-scale workshops. Each cart is adorned with a small clay lamp and a sturdy paper horn mounted on top of it. Two sticks are attached to the cart, producing a distinctive sound when pulled by children. Hence, the name ‘tomtom car.’

The women recount a slump in production due to the pandemic, spanning two years. During this period, they had to pivot to alternative livelihoods to sustain their families. However, with the situation returning to normalcy, they resumed their traditional craft in 2022.

Each cart is adorned with a small clay lamp and a sturdy paper drum mounted on top of it. Photo: Rajib Dhar

“>

Each cart is adorned with a small clay lamp and a sturdy paper drum mounted on top of it. Photo: Rajib Dhar

Among these artisans is Bulbuli, who is about 50 years old. She was born and married in the village. She learned the craft from her father and continues to engage in tomtom toy production.

Bulbuli explained that the workshop is located in her maternal uncle’s house, where her aunt, uncle, and cousin Jafar collaborate in toy manufacturing. Jafar subsequently sells the toys at various fairs.

When asked who does what, Bulbuli’s aunt Maleka Begum replied with a smile, “Is this a work for the men? The women do these jobs. From slicing bamboo to closing the disc, we do everything.”

“Crafting toys begins with the fairs. It begins before Durga Puja and concludes with the Rath Yatra,” Maleka said.

The women make most of the toys, while the men engage in procuring raw materials and selling the toys.

Artisans reveal that each person carries out specific tasks in the toy-making process. On average, they produce 100 toys daily.

The production cost per tomtom is at least Tk6. Wholesale prices range from Tk8 to Tk10 per toy. However, they are sold for Tk15-Tk20 each at the fairs.

Besides tomtoms, artisans also produce various other types of toys, notably bird carts and wooden trucks. Crafting a bird cart costs Tk10, and is sold at a wholesale rate of Tk14. Meanwhile, the production cost of a truck exceeds Tk20.

Jafar Ali, Maleka’s 31-year-old son, joined the conversation. He has gone to numerous fairs, selling his toys. Jafar manages household expenses and prepares new toys by procuring fresh raw materials.

“We are making toys for Boishakhi Mela. We started toy production in February. Till now, we have manufactured 14 thousand pieces,” Jafar said.

“Selling toys by ourselves is more profitable. Wherever there is a fair in the country, we take our toys there. This way, we sell around 50,000 pieces of toys every year,” says Jafar.

There are a few wholesalers in the village who purchase toys and sell them at various districts and fairs across the country. Among them, there’s a businessman named Insan, who says that artisans in each house produce at least 50,000 pieces of tomtoms and other toys per year.

The wholesalers from this village often sell their toys in Dhaka, as there is good demand there. They also sell toys in Barisal, Patuakhali, Cumilla, Chattrogram, and Sylhet.

After talking to 10 villagers, we get to know that there are ten wholesalers in Kholash. Other than that, there are five wholesalers in Dupchanchia, Bus Stand and one in Dhaper Haat. Many people come from outside to buy toys from them.

One of the female artisans is Tahera Bibi. She said, “I have two sons and one daughter. I have been making toys for 30 years. I have married my daughter off with this income. My husband cannot work, and my sons do not take on my responsibilities. I run the family by selling toys. I make Tk70 profit by selling 1,000 toys. I make 1,000-1,200 toys a day. If there was no toy business in the village, how would I have survived?”

“The production cost has increased over time. 12 years ago, a tomtom was sold at Tk5-Tk7,” artisan Nur Islam said.

The traders tell us that there are fairs all across the country throughout the year. Due to high demand, a tomtom is sold at Tk20. An artisan can produce 400 tomtoms each week. The business peaks at Boishakh and slumps during the monsoon.

Jahanara Begum, a housewife, makes tomtom for extra cash. Her husband, Akhtar Molla is a tomtom trader. She says that her husband travels all across the country to sell tomtom. Everyone in her family is an expert at making tomtom.

The Khulosh Gram Khudro Kutir Shilpo Samiti has been formed with 200 artisans in this village. The current president of the association is Ayatur Nur Islam.

He said, “We make only a few types of toys. There is no one to see our plight. The government can give us training so that we can make better toys.”

He added that almost everyone in the village is solvent, but if there is any trouble, there is no support. The villagers have to do everything themselves. No loans are available from any bank for these cottage industries.

“So, even though we want to make more toys, we cannot do it.”

The Deputy General Manager of Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation (BSCIC) Bogura branch, A K M Mahfuzur Rahman told us that he did not know whether there was such an industry at Kholash. If anyone wants, they can take training and small loans from BSCIC, he added.

He said since many artisans are not solvent, they have to inform the authorities about their need for loans. BSCIC will assess their skills and trade, and then will decide about granting them benefits.