Gov. Phil Scott took direct aim on Wednesday at two bills being discussed by the Legislature’s environment committees, calling one an “economic disaster” and saying the other would “put Vermonters in jeopardy of violating laws they don’t even know exist.”

The approach was a surprise to housing developers and environmentalists, they told VTDigger, as they are more united now than any time in recent memory after months of seeking a compromise on the direction of regulatory reform.

Scott criticized H.687, which would expand Act 250’s automatic jurisdiction to a majority of the state, and S.213, a bill that proposes setting up a new statewide program to oversee river systems in response to the summer’s flooding, at his weekly press briefing.

He “won’t accept a housing bill that fails to meet the moment,” he said, indicating that he would likely veto a bill that increases the law’s environmental protections.

But state lawmakers, developers and members of environmental groups say this legislative session holds unique potential to strike a compromise on Act 250 reform that would satisfy both housing developers and environmentalists.

Efforts to reform Act 250 — Vermont’s sweeping land use law — have been ongoing for years.

Historically, developers have argued that Act 250 can cause expensive delays that prevent them from building housing with speed needed for profitability or simply to meet the broadening demand. Environmentalists respond that, in fact, the law should be strengthened in certain areas to protect critical resources, such as forests, from rapidly becoming developed.

Optimism about a potential agreement stems from a working group that met throughout the summer and fall and included a wide range of stakeholders, including housing developers and environmental groups.

“The feeling coming out of those summer study committees is that this compromise is the biggest compromise we’ve seen on Act 250 at this point,” said Megan Sullivan, a lobbyist for the Vermont Chamber of Commerce. The organization is pushing for the construction of more housing to help expand Vermont’s workforce.

By its conclusions, members of the working group agreed on a framework for Act 250 reform that would relax the law in certain areas, with the goal of making it easier to build housing, and tighten it in others, which would preserve pieces of Vermont’s natural environment.

That said, the working group did not iron out all of the details. There are currently four bills circulating in various committees that propose different versions of that framework: H.687, H.719 (which Scott supports), S.308 and the “BE Home Act,” a bill in the Senate Committee on Economic Development, Housing and General Affairs that does not yet have a number.

But the principle of give-and-take was clear.

“Facilitating the development of new housing while ensuring that we are maintaining our rural working lands and ecologically important natural resources are not mutually exclusive goals,” the group’s report reads.

On Wednesday, the governor suggested that was not a statement with which he would agree.

“We cannot let a couple special interests and a couple committees block the progress we need to make,” he said.

When asked to name special interest groups, Scott pointed to the Vermont Natural Resources Council, an environmental nonprofit that has historically argued for strengthening Act 250.

Their mission, he said, “is to protect the environment as best they possibly can.”

“My mission is to make Vermont more affordable, create more housing and make Vermont safer,” he said. “So we have two different missions.”

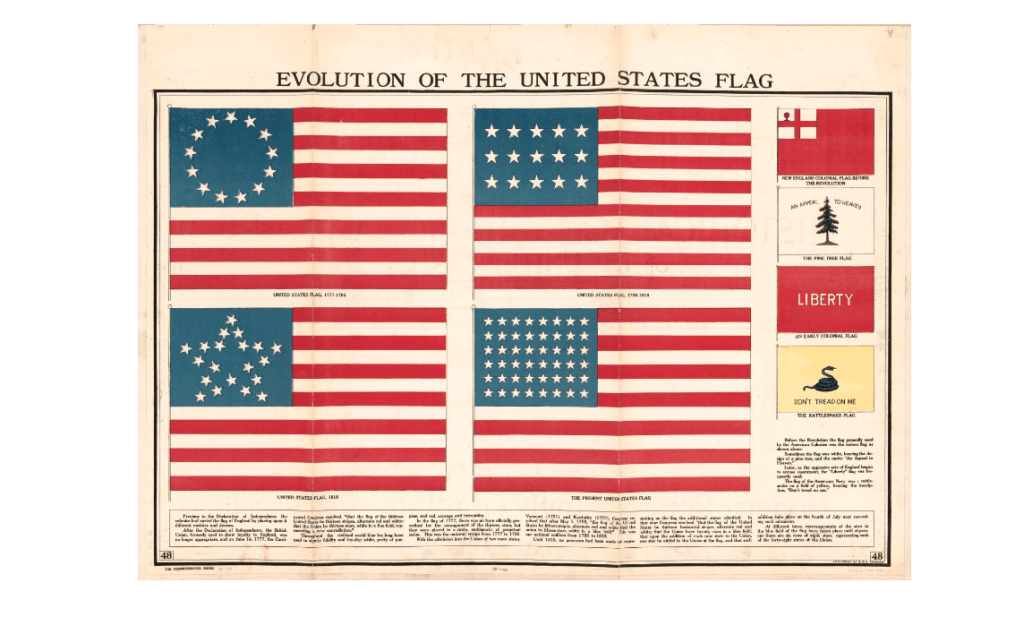

Scott’s message came with props. During his remarks, he presented two large maps: one that showed dots representing Act 250 permits and the other that showed the state mostly colored red, representing the areas that would have Act 250 jurisdiction under the new bill.

The Act 250 bill, which was sponsored by Rep. Amy Sheldon, D- Middlebury, and Rep. Seth Bongartz, D-Manchester, is in the House Environment and Energy Committee, which Sheldon chairs.

On Thursday, at another press event, Sheldon responded to Scott, noting that he “distanced himself from the environment, which was sort of heartbreaking for me.”

“I think, for a Vermont governor to say that the environment was sort of spearheaded by a special interest group — yeah, wow,” she said. “You know, all Vermonters understand that, really, the environment is the heart and soul of who we are.”

Sheldon said she had not closely examined the maps but called them a “firebomb of fearmongering” and said that her proposed expansion is not set in stone six weeks into the session.

She said her committee is just beginning to have a conversation about Act 250 and that H.687, while not a housing bill, eliminates Act 250 review in downtown areas and allows towns to alter Act 250’s jurisdiction to accommodate for growth.

She referred to the working group’s consensus. The group agreed that any reform should support development in compact areas, help grow rural areas in appropriate ways, increase protections for key natural resources, make the permitting process more clear and minimize redundancies with other regulations, according to the report.

The report noted that “the consensus would not remain intact if any individual recommendations were removed from the package.”

Brian Shupe, executive director of the Vermont Natural Resources Council, said Sheldon’s bill would bring “a lot of land under Act 250 jurisdiction,” but that “the process is still playing out. No one has voted on that bill yet.”

Shupe said he was surprised by the governor’s characterization of his organization after its staff spent the summer working with officials from Scott’s administration “on what really became a consensus framework for Act 250 reform.”

Asked about the governor’s comments, Sullivan, with the Vermont Chamber of Commerce, said it’s too early in the session for her to deeply criticize a single bill while “there are a lot of conversations that are happening and getting hammered out.”

There are bills that have been introduced “that aren’t where we would see the compromise being,” she said, but she intends to “continue to have those conversations about what the compromise looks like and how the bills can move to do that.”

Kathy Beyer, senior vice president at Evernorth, a nonprofit affordable housing development company, served on the working group that met over the summer and serves as a board member on the Vermont Natural Resources Council.

She said there is no question that Act 250 can make the development process longer, more challenging and more expensive. When an Act 250 permit gets appealed, that process can take between 12 and 24 months, she said.

“It’s largely a matter of time, but time adds cost,” she said.

Because many of Evernorth’s projects fall under the category of priority housing, Beyer said 80% of them are already exempt from Act 250.

The working group, she said, had some challenging conversations.

“When we started, I wasn’t sure we were going to get to a report,” she said.

Now, she stands behind the consensus and said the agreement makes it impossible for developers or environmentalists to cherry-pick the types of reform that benefit their interests.

“I think one of the most important things you can do for Vermont’s landscape is to answer the question, ‘Where should our housing be built?’ at the same time we’re talking about conserving land or the working landscape,” Beyer said. “You have to answer those questions together.”