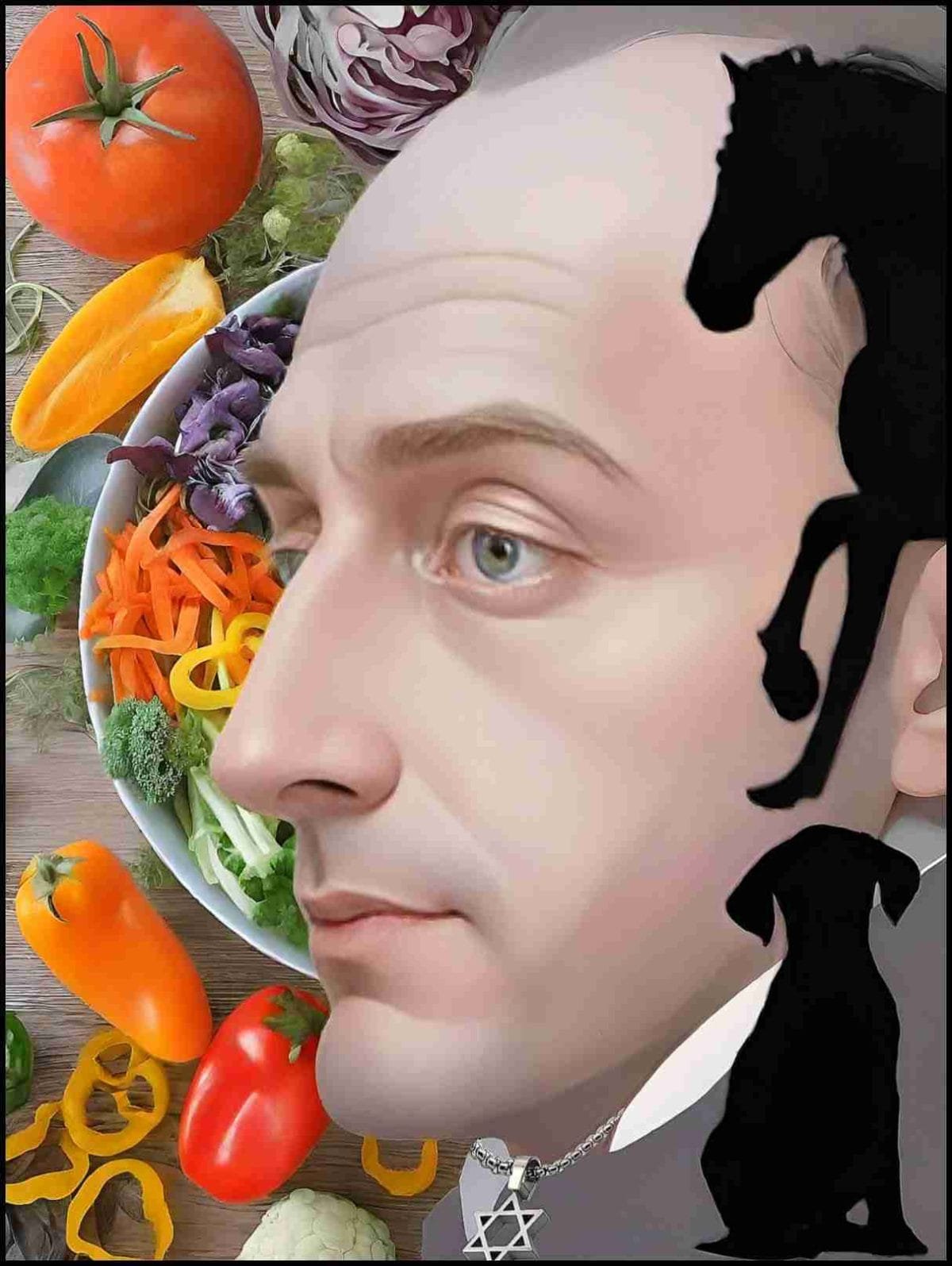

Lewis Gompertz. (Beth Clifton collage)

Lewis Gompertz: Philosopher, Activist, Philanthropist, Inventor

by Barry Kew

Resource Publications c/o

Wipf & Stock Publishers

199 W. 8th Ave, Suite #3

Eugene, OR 97401

One might get the impression from practically all conventional histories of the humane and animal rights movements––which Lewis Gompertz: Philosopher, Activist, Philanthropist, Inventor is not––that neither African-Americans, Jews, nor vegans and vegetarians had anything to do with anti-cruelty activism and building the cause until very late in the twentieth century, if then, decades after the 1975 Peter Singer opus Animal Liberation should have made the Jewish and vegan contributions manifest.

Only post-Singer, conventional histories seem to have it, did Jewish vegan activists found and fund a multitude of organizations so numerous and influential that even to try to list them would run the risk of inadvertently omitting and thereby slighting many who should not be overlooked.

F. Rivers Barnwell of the American Humane Education Society with the Pontiac (1926-1932 vintage) that he drove on his rounds throughout Texas and adjoining states.

(Photo courtesy of granddaughter Evangeline Olive Morris.)

African-Americans more visibly excluded

Even today, histories of humane and animal rights advocacy ignore African-American contributions except to sometimes acknowledge in passing that the founders of practically all of the first humane societies in the U.S. and the United Kingdom were previously successfully involved in seeking the abolition of slavery.

Reality is that there might not even be a humane movement today without the monumental and enduringly influential contributions of African-American humane evangelists William Key, Richard and Seymour Carroll, John W. Lemon, and Frederick Rivers Barnwell.

The Carrolls, father and son, with Lemon and Barnwell, picked up the cause, popularized it throughout the South and Midwest, and carried it forward through the first half of the 20th century, after the founding two generations of humane leadership died out, leaving “humane leadership” in the hands of bureaucrats whose vision––constrained by the experience of the Great Depression––rarely extended beyond winning animal control contracts, operating pounds and pet cemeteries, and quietly building endowments.

Humane historians excluded Jews too

Humane historians excluded Jews too

The African-American contribution to building and expanding the humane cause was quite deliberately and purposefully excluded by William Alan Swallow from Quality of Mercy (1963), the most influential history of animal advocacy to that point.

Swallow’s lifelong companion Eric Hansen, made president in 1942 of the Massachusetts SPCA and American Humane Education Society, had within a year of his arrival purged Seymour Carroll, John W. Lemon, and Frederick Rivers Barnwell from American Humane Society employment.

(See Black humane history found in great-grandpa’s attic near a town called Ark and Four black leaders who built the humane movement.)

Swallow, Hansen, and Hansen’s early career patron Sydney Coleman, whose 1924 volume Humane Society Leaders in America was before Quality of Mercy the most influential history of the humane movement, had comparably purged any mention of the role of Jews in founding the building the cause. Swallow continued the omission.

(See How “Quality of Mercy” Swallowed the humane movement (part 1) and How “Quality of Mercy” Swallowed the humane movement (part 2).

John Hoyt and Paul Irwin

(HSUS photo)

Christians dominated leadership

For most of the 20th century the leaders of the American Humane Association were primarily devout Catholics; the leaders of the Humane Society of the U.S., founded in 1954, were from 1970 to 2004 the former Protestant clergymen John Hoyt and Paul Irwin.

No Jew appears to have held a prominent position with either organization, nor with the American SPCA, until then ASPCA president John Kullberg, a Catholic, in 1986 hired attorney Madeline Bernstein. Bernstein has headed SPCA Los Angeles since 1994.

Wayne Pacelle, also Catholic, hired and promoted the first Jews to hold prominent positions at the Humane Society of the U.S. early in his tenure as president, 2004-2018.

Newswire photo dated April 23, 1933: “Mrs. Diana Belais pins medal on Beans, a mixed terrier owned by Mrs. William Hunninghouse, at Animal Hero Day in Wanamaker auditorium. Beans saved the Hunninghouses from gas. Nellie (center), owned by Elizabeth Stezelberger, barked a fire alarm. Jean Day (right) displays Pekoe Sin.”

David & Diana Belais

ANIMALS 24-7 has previously detailed the hugely influential work of Jewish jeweler David Belais (1863-1933), who in 1893 founded the Humane Society of New York (formally incorporated in 1904), and his wife, Diana Belais (1870-1944), who emerged as an outspoken antivivisectionist in 1889, at age 19.

Diana Belais went on to found The Open Door, an animal welfare magazine, in 1895, published until 1938; founded the New York Anti-Vivisection Society circa 1908; founded the Legion of Hero Dogs in 1932; and in 1921 founded the short-lived First Church of Animal Rights.

(See “Intersectional issues” broke up the 1st Church of Animal Rights––in 1921.)

Dissolving the New York Anti-Vivisection Society in 1935, Diane Belais fought and won a three-year court battle to redistribute the substantial assets of the society to other animal advocacy organizations to help them survive the Great Depression.

Diana Belais then remained active for animals as a concerned individual until her death.

Henry Spira’s 1976 campaign against cat sex experiments at the American Museum of Natural History was the first to stop a federal funded animal experiment in progress.

Henry Spira

Investigating what became of the $460,000 R.M.C. Livingston estate, left to the defunct New York Anti-Vivisection Society in May 1945, was among the first involvements in animal advocacy of Henry Spira (1927-1998).

A Jewish survivor of Krystalnacht, November 9-10, 1938, when Nazis launched pogroms against Jews throughout Germany and Austria, Spira hosted Peter Singer as a houseguest while Singer wrote Animal Liberation, then formed Animal Rights International.

Animal Rights International in 1976-1977 and 1980 won the first recognized campaign victories of the late 20th century animal rights movement.

(See Henry Spira, 71, founder of the animal rights movement.)

Alex Hershaft in 2000. (FARM photo)

Alex Hershaft

The late 20th century animal rights movement exploded into the present constellation of national organizations waging a multitude of simultaneous campaigns in 1981, after Holocaust survivor Alex Hershaft founded the Farm Animal Rights Movement and began hosting annual National Animal Rights Conferences that spun off dozens of other local & national organizations.

(See Nellie Saiom Shriver, 80, introduced Alex Hershaft to vegan activism.)

Conventional animal rights movement history holds that Spira, Hershaft, and the many Jewish founders of animal rights organizations who followed them were inspired largely by Singer, but simple reality is that mainstream humane work was at the time not open to Jews.

If Jews wanted to advance animal advocacy, they had no choice but to find new directions.

Leonardo Da Vinci.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Gompertz was Da Vinci-like inventor

Underlying the work of all of the above, including much of the work of the overt anti-Semites in animal advocacy, whether they knew it or not, were foundations built by the Leonardo Da Vinci-like Jewish vegan activist and inventor Lewis Gompertz (1784-1861).

Had Gompertz patented and marketed his most successful invention, the expanding chuck, as author of Lewis Gompertz: Philosopher, Activist, Philanthropist, Inventor Barry Kew mentions in passing, the humane cause might never have wanted for money.

The major credit instead went to one Alexander Bell and T. Hack, who separately developed three-jawed and four-jawed chucks in 1819.

(Wikipedia image)

Expanding chuck

An expanding chuck is the part of a lathe or a drill that enables the user to exchange one bit or other revolving tool, such as a brush or a grinding wheel, for another.

A refinement of the expanding chuck is the vehicular transmission.

Having apparently little interest in machine tools, Kew says little about how important and ubiquitous the expanding chuck became in facilitating the Industrial Revolution.

Suffice it to point out, however, that no house, car, aircraft, nor any other part of life as the developed world has known it over most of the past two centuries has been accomplished without the frequent use of expanding chucks, including the invention and ongoing expansion of computerization.

Barry Kew

Barry Kew

Gompertz, however, as with most of his inventions, was content to put the expanding chuck into the public domain, for the betterment of the world, he hoped, never to claim a penny for thinking of it and producing and publishing the mechanical drawings showing how to realize his insight.

Barry Kew, the back cover of Lewis Gompertz: Philosopher, Activist, Philanthropist, Inventor explains, “is an independent researcher/writer,” who “has also been a teacher, a local group co-organizer/campaigner, general secretary of the Vegan Society, editor of The Vegan, author of The Pocketbook of Animal Facts & Figures, co-author of The Animal Welfare Handbook, and founder and editor of the former Critical Society e-journal.”

What Kew is not, unfortunately, is fluent in translating meticulously researched information gleaned from more than 500 footnoted sources into a narrative which, by itself, might attract a substantial readership to this first long overdue full-length biography of Lewis Gompertz.

Leonardo DaVinci’s design for a helicopter.

Helicopter

Gompertz was, quite simply put, the single most influential individual in humane, animal rights, and vegan history, albeit almost unknown to any but about as many historians and scholars as might fit into a large helicopter.

Yes, Gompertz, like Da Vinci, also left behind a description and mechanical drawings for a helicopter, envisioned in 1814, 125 years before Igor Sikorsky made the first experimental helicopter flight on September 14, 1939.

Lewis Gompertz.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Bicycle

Gompertz also attempted to invent the bicycle, as an alternative to horse transportation, after the German Baron von Drais, Kew recounts, “created his contraption [a proto-bicycle] in 1817 as a horse substitute because, it is now believed, the price of oats and everything else had soared after the planet was plunged into darkness following the volcanic eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora in 1815; the next year was known as the Year Without A Summer.

“Horses starved because of lack of fodder.”

Gompertz tried to improve the von Drais “contraption” in 1820, but first successful bicycle was not developed until the Parisian blacksmith Pierre Michaux invented, in steps between 1863 and 1869, the first bicycle resembling a modern bicycle.

Lewis Gompertz’s “walking wheel,” 1820.

Ancestry & philosophy

Putting Gompertz’s role as moral philosopher first in his title, Kew devotes 20 pages to his acknowledgements, definitions of terms, and introduction, much and perhaps most of which might have been incorporated into a story line.

(That this review also has a lengthy introduction must be admitted.)

Kew then expends 33 pages on an analytical review of Gompertz’s 1824 tome Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man & of Brutes.

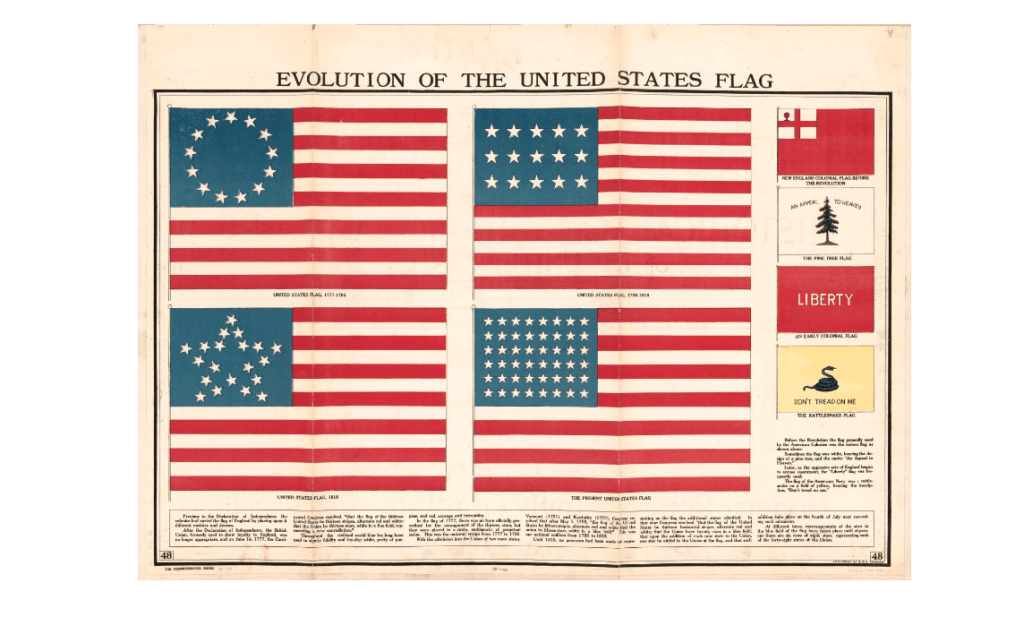

Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man & of Brutes expanded considerably upon Humphrey Primatt’s A Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy & Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals, which might be regarded as the second most influential revolutionary document of 1776, after the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

Tom Regan.

From concept to application

Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man & of Brutes might also be considered directly ancestral to Animal Liberation and The Case for Animal Rights (1983) by Tom Regan, which are generally considered the philosophical foundations of contemporary animal rights advocacy.

(See Tom Regan, 78, made the case for animal rights.)

But in truth hardly anyone outside of academia––and for that matter, hardly anyone within academia––really gives an expanding chuck-using tinker’s damn about the nuances of animal rights philosophy.

What most people who consider themselves for or against “animal rights” give a damn about is how the concept translates into practical application, whether to prevent and prohibit distressing cruelties, or to be ridiculed and flouted in order to continue those cruelties.

“Humanity Dick” Martin in 1824 won the first British cruelty conviction after presenting an abused donkey as evidence––trumpeted by the media of the day as having called the donkey as an expert witness.

Formation of the SPCA

Lewis Gompertz became involved in the formation of an organization called the Society for Protection of Brute Animals From Cruelty on June 16, 1824, at a coffee house meeting convened by the Reverend Arthur Broome and probably Charles Wheeler, a man Broome had personally employed to investigate cruelty cases after the 1922 passage of Richard Martin’s Act, the first British law prohibiting cruelty to animals.

Richard Martin himself (1754-1834) was in attendance, along with William Wilburforce (1759-1833), a fellow Member of Parliament better known introducing the Slave Trade Act of 1807, the first legislative step toward achieving the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire.

Martin and Wilburforce had joined with Broome in previous failed attempts to form a humane society in 1820 and 1821, before Martin’s Act gave animal advocacy organizations the ability to prosecute cruelty cases.

William Wilburforce, British politician and philanthropist. (Beth Clifton collage)

William Wilburforce

At that point the Society for Protection of Brute Animals From Cruelty, a name later shortened to Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, could of necessity have only done humane education and general advocacy.

This was the direction that Broome and most of the other cofounders of the SPCA favored all along, in conflict with Gompertz, who was simultaneously the major financial benefactor of the SPCA and favored aggressively pursuing criminal prosecutions.

Gompertz especially clashed with Wilburforce, described by Kew as “an anti-radical and member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, who advocated change in society through Christianity and improvement in morals, education, and religion, fearing and opposing radical causes and revolution.”

Wilburforce, Kew notes, “had also been a founding member of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews, in 1809.”

Jesus driving the buyers and sellers of sacrificial animals from the Jerusalem temple, painting by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1609-1664).

“The Society should be conducted exclusively on Christian principles”

Eventually the SPCA “resolved it was indispensably necessary that the Society should be conducted exclusively on Christian principles,” Kew reports, after a decade of ongoing conflict with Gompertz on just about everything coming before the society.

As Kew details, an anti-Gompertz periodical called Voice of Humanity appeared in 1830, shortly followed by the 1831 formation of the Association for Promoting Rational Humanity towards the Animal Creation (APHRAC).

APHRAC, which might be termed overtly “welfarist” and conservatively “welfarist” at that, faded from view in 1833-1834, after Gompertz was drummed out of the SPCA in 1832 for the alleged twin offenses of being Jewish and a Pythagorean.

Pythagoras. (Beth Clifton collage)

“What was a Pythagorean?

This is what vegetarians and vegans were then called, for want of any more precisely descriptive term, in reference to the Greek mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras (circa 570 BCE to 495 BCE), who founded a proto-vegetarian commune circa 530 BCE near Croton, Italy.

Gompertz might have sought allies among fellow “Pythagoreans,” but apparently did not.

The Reverend William Cowherd (1763-1816) promoted vegetarianism from 1809 to the end of his life, as did his ministerial successor Joseph Brotherton, who founded the Vegetarian Society in 1847.

Gompertz, however, “was vegan in his rejection of blood sports, vivisection, animal labor, and animal exploitation generally,” while the Brotherton congregation, like Cowherd, were chiefly concerned with maintaining good health and personal purity.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Vegan but anti-purist

The Vegetarian Society grew to 376 members by 1849, but Gompertz scolded them because they were not vegan, a term not actually coined until Donald Watson (1910-2005) spun off the Vegan Society in 1944, and because the Vegetarian Society discouraged use of “wine, spirits, tea, coffee, sugar, salt, oil, vinegar, and all condiments.”

Gompertz correctly predicted that vegetarianism would not gain favor among most of the public until the adherents became less purist and more accepting of practices which did not harm animals.

Almost immediately after exiting the SPCA, which was not yet the Royal SPCA, Gompertz formed the Animal Friends Society, with friends including the Catholic physician Thomas I.M. Forster (1789-1860) and the chocolatier John Cadbury (1801-1889).

(Beth Clifton collage)

“Are Christians the only cruel persons?”

A far more active organization than the SPCA ever was, the Animal Friends Society engaged in more than 3,000 prosecutions during the last 30 years of Gompertz’s life.

The Animal Friends Society from the beginning favored activism over moralism.

Wrote Gompertz himself, “The expulsion of persons and tracts, because not exclusively of or founded on Christian faith, must strike everyone with its enormity.

“Are Christians the only cruel persons? Why cast so odious a slur on so enlightened and virtuous a class? Is it them alone who stand in need of reproof?

(Beth Clifton collage)

“Protect dumb creation against every sect”

“Our business is to protect the dumb creation against every sect, and teach humanity to Jews, Mahometans, Deists, and even atheists, as well as to Christians.

“To prove a truth to a Mahometan, by the light of the gospel, would be a vain attempt,” Gompertz railed on.

“He would reply, what is the gospel to me? Show it to me by the Koran, and I will believe you. The Jew would require the Law of Moses. The Deist, the law of nature. And the atheist could not, in common with the rest, refuse the law of moral sense.

“What cares a baited bull whether his tormentor be a professed Spanish Roman Catholic, or English Protestant? We treat not with sects, we treat with mankind.”

(Beth Clifton collage)

The Pease Act

Gompertz and the Animal Friends Society helped in 1835 to secure passage of the Pease Act. Authored by Joseph Pease, 1799-1872, a railway pioneer who became the first Quaker allowed to sit in Parliament, the Pease Act amended the Martin Act to prohibit “the keeping of premises for the purpose of staging the baiting of bulls, dogs, bears, badgers” or “other Animal (whether of domestic or wild Nature or Kind).”

Gompertz next preceded the SPCA and every other animal advocacy society in attempting international outreach.

(Beth Clifton collage)

“No cruelty in India except by the Brits”

Summarizes Kew of the 1836-1837 Animal Friends Society periodical, “A postscript reports that the Animal Friends Society had lately made unsuccessful attempts to establish branches in America, Denmark, and the East Indies.

“Animal Friends Society agents in India had been advised that no cruelty to animals was generally practiced in that country, excepting that committed by the English there.”

The referenced Animal Friends Society agents may have been the former British military officers who around that time visited the 400-year-old Ahmedabad Dabla Pinjarapol, a sanctuary for aged cattle and other working animals, and brought back to England the concept of animal sheltering.

Queen Victoria and her Pomeranians.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Queen Victoria was not amused

Gompertz maintained a reputation for impolitic written expression of his views in favor of animals and against those who abused them.

“Much of Gompertz’s contemptuous output [about blood sports] would have gained him few friends among the wealthy, royalty, and the SPCA, yet he persisted,” Kew observes.

For example, Gompertz wrote, “Often has the Animal Friends Society, while engaged against bull-baiting etc., been charged with partiality to the higher classes, from a supposition that it is the sports of the poor alone which excite its hostility, but than which nothing can be farther from the truth. The hunting of a harmless deer or a fox for mere amusement, though forming a principal diversion of princes and nobles, being equally with bull-baiting a subject of abhorrence to the Society.”

Adds Kew, “The SPCA was awarded the Royal prefix in 1840. Perhaps Victoria and/or her advisors had not been amused by” Gompertz’s criticism.

(Beth Clifton collage)

“Persons of rank trampling”

At some point in 1840, Gompertz pronounced himself “sorry enough to find plenty of persons of rank trampling on every being of inferior power. It has been said that even our two highest individuals patronize hunting and racing…We have received several letters,” Gompertz said, “from highly respectable quarters, pointing out the severity of pace at which the royal carriages travel. The exhausted state of the cavalry and carriage horses, composing the royal cavalcade, as it passed through Hyde Park on Saturday last from Windsor, was truly distressing to all who witnessed it.”

Suggests Kew, “Depending on when exactly in 1840 the SPCA became the RSPCA, this material may have either lost the royal support Gompertz thought [the Animals Friend Society] deserved, or was an expression of his increasing frustration.”

(Beth Clifton collage)

Gompertz vs. the Vatican

That humiliation hardly cured Gompertz of his propensity for challenging authority.

“On November 2, 1846,” narrates Kew, “Gompertz and the Animal Friends Society foreign secretary, the Catholic Dr. Forster, sent an address to the Pope, encouraging him to cause a prevention-of-cruelty-to-animals society to be founded at Rome, and ‘praying his Holiness to prohibit the cruel sports of the bull-ring in Spain, and the inhumanity practiced toward animals in the streets of Rome.”

However, Kew continues, “Pope Pius X forbade the opening of an animal protection office in Rome on the grounds that human beings had no duties to animals.”

Pope Pius IX with a cat.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Something tangled

There appears to be an error of some sort here. Kew seems to have correctly summarized his sources, but Pope Pius IX, immediate predecessor to Pope Pius X, had only just taken office in 1846. Piux X did not succeed Pius XI until 1878.

Pope Pius V in 1567 had already issued a papal bull condemning bullfighting and other forms of animal fighting for entertainment as “cruel and base spectacles of the devil,” making bullfighting promoters subject to excommunication.

Pope Pius IX reiterated the 1567 bull in 1846, early in his papacy, which ended with his death in 1878.

By then the oldest known Italian animal charity, founded in 1871, had already formed. It received the current title, the Ente Nazionale Protezione Animali, from the dictator Benito Mussolini in 1938, after he forcibly merged about two dozen other animal charities into it.

Regardless of the views of Pius X, whatever they were, Pius XII meanwhile cited the proclamations by Popes Piux V and IX in 1940, refusing to meet with a delegation of bullfighters.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Accused RSPCA of “sitting on funds”

Gompertz also denounced his former treacherous associates, complaining in 1847, for instance, that “The now wealthy RSPCA is sitting on funds rather than using them to tackle cruelty; it has disappointing levels of effectiveness and efficacy; it makes inaccurate and false claims, to the Animal Friends Society’s detriment; it is fearful of failure, resulting in inertia; [and] it pays ‘extreme and intrusive adulation to nobility and rank,” summarizes Kew.

Gompertz’s criticisms resembled those voiced since 1969 by British author, animal advocate, and sometime Royal SPCA board member Richard Ryder, whose 1971 volume Animals, Men and Morals: An Inquiry into the Maltreatment of Non-humans was the immediate provocation for the book review by Peter Singer that evolved into Animal Liberation over the next four years.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Cheated by “fundraisers”

As Gompertz aged, the Animals Friend Society, especially in 1848-1849, Kew indicates, was victimized by men purporting to collect funds in the name of the society, but actually pocketing the money.

Named by Kew were scoundrels named John Jeffrey, John Perry Henning, Henry Roberts, and Thomas Croton.

When Gompertz managed to bring charges against Henning, Kew recounts, the Evening Mail described him as “a miserably dressed decrepit old Jew,” in apparent derogatory reference to Gompertz’ refusal to wear either leather, fur garments, or wool.

“The prisoner Henning objected to the witness being sworn until examined,” the Evening Mail continued, “observing that he [Gompertz] held infidel principles…Gompertz, who professed himself a Jew, admitted he did not believe in a future state of rewards and punishments.”

Henning, sentenced to serve a year in jail on that occasion, in 1853 received an 18-month sentence for stealing from a later employer.

Lewis Gompertz.

“Victim of a destructive Christian animal welfare campaign”

“For close to 28 years,” Kew wraps up, “Gompertz had been the victim of a destructive Christian animal welfare campaign…He fought hard for a more enlightened society, even though the largely Christian darkness almost closed over his and others’ vegan ethic for decades.

“He and his Animal Friends Society inspectors went beyond prosecuting: school talks, circulation of pamphlets, tracts, and notices, Animal Friends Society Reports, abstracts of Pease’s Act 1835, publicizing, collecting donations, preventing and exposing cruelties, rescuing animals, forming new branches, holding meetings, press announcements.

“It has been hinted by the Animal Friends Society work recounted here,” Kew suggests, “what Gompertz might have done at the SPCA, given the support, the chance for expansion, not least of minds, and a lack of self-serving interference, snubbing, and obstruction from others.

(Beth Clifton collage)

Difficult to understand now?

“The relentless, sometime anti-Semitic, full-time anti-Pythagorean, only-select-Christians-are-rational-and-compassionate bigotry he suffered is perhaps difficult to understand now,” Kew concludes.

Well, not really.

Direct influence from organized Christianity is much less evident in animal advocacy today, but anti-vegan, anti-vegetarian, and anti-Semitic bigotry remain as evident as ever, along with what might be most politely described as a persistent lack of communication with animal advocates of color.

(See sub-menu Black history & animals.)

Henry Salt.

Successors

“From circa 1894,” picked up historian and vegan animal advocate John F. Edmondson in a recent Facebook post, “Ernest Bell took over the running of the Animals’ Friend Society with Edith Carrington and others. Jessey Wade joined them circa 1898. The same team managed The Humanitarian League with Henry S. Salt.”

Salt (1851-1939), is credited, as Wikipedia puts it, “with having been one of the first writers to argue explicitly in favour of animal rights, rather than just improvements to animal welfare, in his Animals’ Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress (1892).”

Beth & Merritt Clifton

“When Ernest Bell died in 1933,” Edmondson finished, “Jessey Wade merged the society with the National Council for Animals’ Welfare — the project of Gertrude Baillie-Weaver and Harold Baillie-Weaver. During World War II, they moved the headquarters from London to Manchester.”

The National Council for Animals’ Welfare was disbanded in 1983.

Karen Davis, Ph.D., United Poultry Concerns founder, dead at 79

Karen Davis, Ph.D., United Poultry Concerns founder, dead at 79 A Traitor To His Species: Henry Bergh & The Birth Of The Animal Rights Movement

A Traitor To His Species: Henry Bergh & The Birth Of The Animal Rights Movement Money, power, & farmed animal advocacy: Jeff Thomas tells all

Money, power, & farmed animal advocacy: Jeff Thomas tells all More Than a Meal: Thanksgiving, turkeys, tradition & Karen Davis

More Than a Meal: Thanksgiving, turkeys, tradition & Karen Davis Why did the ASPCA pres get $966,004, while we got $9.70 an hour?

Why did the ASPCA pres get $966,004, while we got $9.70 an hour? Hearts out of place: transplants, pigs, chickens, “victories” & McDonald’s

Hearts out of place: transplants, pigs, chickens, “victories” & McDonald’s