In 1976, President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month as he called upon the public to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” Since then, every United States president has recognized the month.

As children, many of us would celebrate Black History Month in school by learning about people like Martin Luther King, Jr. or Rosa Parks. If we were lucky, we might even be taught about people like Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, or Pauli Murray. While we celebrated Black history, many of us never heard much about the father of Black History Month, Carter G. Woodson.

Woodson was born in 1875, 10 years after the end of chattel slavery in America. As a descendant of enslaved people, he believed younger generations needed to know their history and what Black people in America had overcome. As he wrote in his seminal 1933 book, The Mis-Education of the Negro, Woodson believed that it was particularly important that Black people be the teachers of their own history and not be reliant on those who had oppressed them.

After becoming the second Black person in America to earn a PhD from Harvard University, Woodson made it his mission to preserve the study of Black history and mentor younger Black scholars. His home in Washington, DC, became the headquarters of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which is now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), and where the first Negro History Week was held in 1926.

“We should emphasize not Negro History but the Negro in History. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hatred and religious prejudice.”

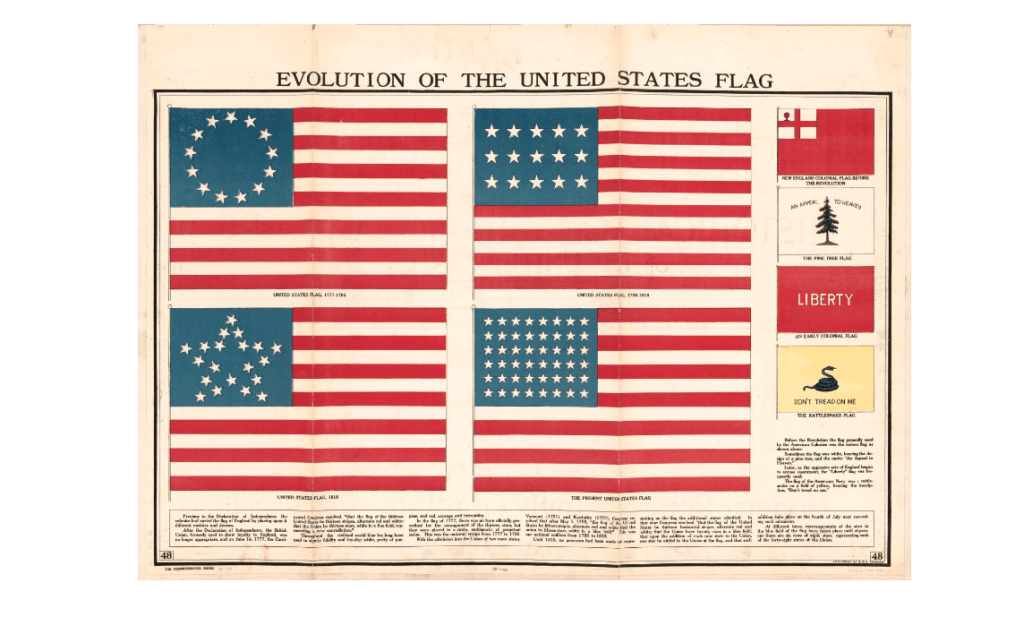

Woodson intentionally chose February to celebrate Black history because he wanted it to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. After Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, Black communities had taken to celebrating the former president’s birthday, and since the late 1890s, Black communities had also celebrated Douglass. Woodson wanted to build on this tradition, and he also wanted to extend it from being about two men to being about the strides of the Black race as a whole.

Woodson believed that history was made by people as a collective and not just individual actors, so while he admired both Douglass and Lincoln, he urged everyone to go deeper and reflect on Black people’s broader role in the Civil War—how it took hundreds and thousands of Black soldiers and sailors to fight for their freedom and secure their own destiny.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ’s newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Beyond Black History Month

[Woodson] thought that…Americans as a whole would learn about Black history daily….We have not yet reached that point.

Speaking of the purpose of the week at the time, Woodson said, “It is not so much a Negro History Week as it is a History Week. We should emphasize not Negro History but the Negro in History. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hatred and religious prejudice.”

When Woodson unveiled Negro History Week in 1926, there was a vast response. To meet the demand, Woodson and ASALH provided study materials to schools across the country. ASALH also formed branches to help meet the needs of local areas. In 1937, at the urging of educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune, Woodson created the Negro History Bulletin, a monthly newsletter sent out to high school teachers to provide lesson plan ideas on Black history. The bulletin still exists today as the Black History Bulletin.

Woodson wanted students to learn about the information presented in the bulletin throughout the year. He knew teaching Black history was necessary, but it could not be limited to a week. He thought that the weekly celebrations of Black history would eventually come to an end, and that Black people—and Americans as a whole—would learn about Black history daily. Today, with ongoing attacks against the teaching of a truthful history in schools, we have not yet reached that point.

It is essential for us to remember the role that Black people have played in shaping history—not just Black history, but American history.

Woodson died in 1950. At the time of his death, the Civil Rights Movement had not yet been born. Rosa Parks had not yet refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus, Martin Luther King, Jr. had not yet been arrested for civil disobedience, Fannie Lou Hamer had not yet proclaimed that she was “sick and tired of being sick and tired” and many of us had not yet reaped the freedom we enjoy today because of the work of many of these leaders.

Now more than ever, as Woodson urged us to do, it is essential for us to remember the role that Black people have played in shaping history—not just Black history, but American history. As we celebrate this month, it is important to acknowledge this history all year long.